When people think about Taiwan, they often ask what language is spoken there. Those who know little about Taiwan will assume people in Taiwan speak “Taiwanese” (makes sense as people from England speak English and people from Spain speak Spanish.) Those who know more about Taiwan will think people speak Mandarin/Chinese (makes sense as people from America speak English and people from Mexico speak Spanish.)

While people in Taiwan now predominantly speak Mandarin due to government policies and education, there has been an increase in interest to preserve and spread Taiwan’s mother tongues since the 2000s, including Taiwanese Hokkien:

- In June 2017, Taiwan passed the Indigenous Languages Development Act, which officially designated the languages of the country’s 16 recognized indigenous tribes as national languages. This was an act to promote and further efforts to protect the nation’s diverse aboriginal cultures and facilitate transitional justice for indigenous peoples.

- In December 2018, Taiwan passed the National Languages Development Act, to grant equal protections to all national languages and guarantee the right of citizens to use them in accessing public services. According to the law, “national languages” refers to the mother tongues of local ethnic groups, such as Hakka; Holo, also called Taiwanese; indigenous languages, as well as Taiwan Sign Language.

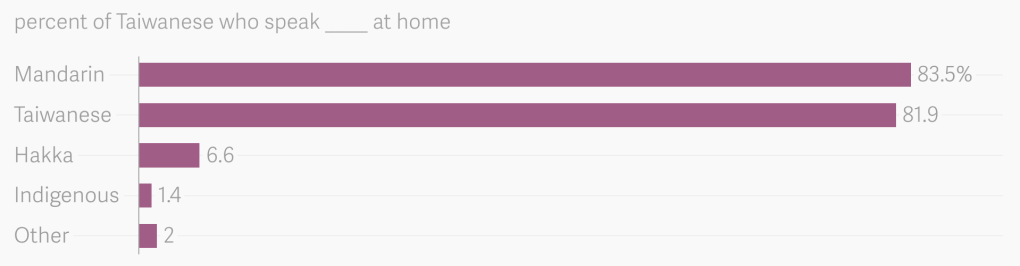

Taiwan 2010 Census

So, what exactly is Taiwanese? What about Hokkien or Southern Min? Here is a clean and simple explanation from the awesome podcast, Bite-Size Taiwanese:

Taiwanese (Tâi-gí,臺語) refers to the language that is spoken by a large majority (roughly 70%) of the population on the island nation of Taiwan. While Mandarin Chinese is the official language of Taiwan, Taiwanese has recently gained national language status along with Hakka, followed by 16 aboriginal languages. This allows access for public services in these languages, provides funding for radio broadcasting, television shows, films, and media publications, and provides additional resources for elective courses in the primary and secondary education system.

In the English-language media, Taiwanese often gets referred to as Hokkien or Southern Min. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they technically refer to different levels within a linguistic family tree.

Specifically, Taiwanese refers to a group of Hokkien-variants that together with the history, society, and environment of the island have mixed and evolved over centuries including influences from Japanese. Other variants of Hokkien found in Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia have also developed independently according to their histories and have absorbed vocabulary from neighboring languages.

Southern Min is a broader category that besides Hokkien includes Teochew and Hainanese. Southern Min, in turn, belongs to the broader grouping of Min, which is one of the big seven language groups of the Sinitic languages (the others being Mandarin, Yue, Hakka, Wu, Gan, Xiang). As a rough comparison, differences among these seven groupings are greater than those for the Romance languages. In fact, even just within the Min language group, speakers from languages of different branches may have a hard time understanding each other.

**We will continue referring to the Taiwanese language as “Taigi” for ease of use and clarity, but this is not to be mistaken that Taigi is by any means the “true Taiwanese language.”

Why do Taiwanese people speak Hokkien?

Prior to the Japanese imperial rule over Taiwan in 1895, many people from southern China traveled and stayed in Taiwan. These people spoke the languages of their respective villages, which were mostly Hokkien and Hakka. This means most people of the Han ethnicity typically spoke these languages. However, due to the lack of a formal government or organizations to promote them, the written form of these languages are not standardized nor wide-spread.

Why do very few people speak Taigi?

While languages like Hokkien and Hakka were prominent even during Japan’s rule of Taiwan, the languages were aggressively replaced after the Japanese government left Taiwan. Today, many kids, especially those in Taipei, have lost the ability to speak the mother tongue that their parents and grandparents speak.

Why is this?

Government

When the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) came to Taiwan and took over the government from Japan, they wanted to rid the Taiwanese people of Japanese culture, including the language. Taiwanese youth and many adults learned to speak Japanese for school and to conduct business. To counteract this, the KMT-run government, Republic of China (ROC), enforced Mandarin Chinese as the national language. This would mean all government officials, standardized tests, and legal documents were to be all written in Mandarin. The most prominent way to spread Mandarin is through education.

Education

Since Mandarin was to be used as the national language, this had to be taught in schools. With the ROC government, all teachers were from China and their Mandarin became the new standard. While the teaching material was in Mandarin, there was also a level of promotion that came with speaking Mandarin and squashing of Taiwan’s mother tongues, such as Taigi and Hakka. If caught speaking Taigi or Hakka in school, students would be forced to wear a sign around their necks that said, “I love speaking Mandarin,” and would have to catch the next guilty student to pass it onto. This created major ostracization between kids and the aversion to speaking/learning Taigi.

Media

In the 1970s, the first airing of hand puppets (布袋戲) was televised. This was extremely popular and families would enjoy watching the performances together. The dialogue was mainly spoken in Hokkien. The government wanted to utilize its widespread popularity to propagate their ideas, so they added a new character named, “China Strong (中國強),” who would enter scenes while singing his theme song in Mandarin. Despite adding this character, the popularity of the show was not to be ignored. Therefore, in 1974 the government shut down the show to further restrict access to Hokkien media. They even implemented certain policies to prohibit Taiwanese to be on air. For example, only one hour out of the daily 24 was allowed for Taigi programs and no more than two Taigi songs could be played.

As the 90s rolled around, many live-action shows and movies starred Mandarin-speaking characters. The good-looking and important characters spoke in Mandarin, while the ugly, evil, dirty and/or older characters would speak in Taigi. Professions such as doctors, lawyers and business people would speak Mandarin while farmers, gangsters, and the homeless would speak Taigi. This kind of media portrayal and unfair representation further contributed to the youth of Taiwan not wanting to speak Taigi.

Family

A common stereotype is that people who grew up in Taipei do not know how to speak Taigi. As Taiwan entered its economic golden ages in the 80s and 90s, the importance of business and having a proper education grew. This meant that parents had to become more fluent in Mandarin, and make certain that their kids were even more proficient in order to be successful.

Many parents and grandparents used their linguistic advantage to speak about “adult” topics in Taigi. This became their secret language so they never taught it to their children.

“You can’t write in Taiwanese”

Taigi is often referred to as a dialect because of its lack of a standardized written system. However, it is to be noted that any language that started out spoken can be followed by a written system. Although various writing standards have been offered by local organizations and scholars for more than 150 years, no government authority in Taiwan has accepted these as an educational standard for teaching Taigi. Now, with a resurgence of wanting to preserve Taiwanese, new systems are being set out.

There are dozens of ways to write in Taigi–using one or more of Latin, Chinese, Japanese, or Korean symbols. Each of these scripts come with their respective writing systems. The most common scripts used today are Chinese and Latin characters.

Mandarin Characters

While writing Taigi using Mandarin characters is possible, it can sometimes be tricky to read or understand by people not familiar with Taiwanese. This is because the characters used to write a Taigi word are not always the same characters used in the Mandarin equivalent. For instance, the characters for “right hand” are as follows:

右手 (yòu shǒu)

in Mandarin Chinese

正手 (chiàⁿ-chhiú)

in Taigi

The Taigi version uses the character 正 which also means “right,” but with the definition of “correct” rather than the directional “right.” The cultural and semantic nuances which Taiwanese people wish to convey about certain topics can be inferred through the selection of Chinese characters as seen above.

Latin Characters

There are two major camps of romanization for Taigi: Pe̍h–ōe–jī is (POJ) and Tâi-lô (TL).

TL was derived from POJ so their systems are very similar. See the corresponding letters used:

| POJ | a | b | ch | chh | e | g | h | i | j | k | kh | l | m | n | ⁿ | ng | o | o͘ | p | ph | s | t | th | u |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL | a | b | ts | tsh | e | g | h | i | j | k | kh | l | m | n | nn | ng | o | oo | p | ph | s | t | th | u |

POJ was designed as a native orthography, and is meant to be written and read on its own without Chinese.

TL is a modified version of POJ, intended for use as a PinYin system, with its usage mainly limited to dictionaries and words that do not have corresponding Chinese characters.

Pe̍h-ōe-jī (POJ)

POJ was first created by Spanish missionaries who wanted to spread Christianity to people in the Southern Min region. POJ was used as religious text, literature and/or both:

Taiwan Church News was founded by Thomas Barclay

Since the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was pushing for Mandarin as China’s official language and the ROC was also enforcing Mandarin in Taiwan, POJ publications were banned.

Tâi-lô (TL)

TL was developed by Taiwan’s Ministry of Education in 2006 and promoted as the official phonetic system. There is a closer correlation between TL and the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), such as using “ch” for the more IPA-common sound written as “ts”.

Rules for changing POJ to TL (reverse for the other way around):

- o͘ → oo (the POJ is an o and separate raised dot)

- ch → ts

- chh → tsh

- oe → ue

- oa → ua

- ek → ik

- eng → ing

- ⁿ → nn (the POJ is a raised n. Like “to the power of n”)

There are many debates about which system to use, but their small differences make the two relatively interchangeable. Youtuber 阿勇台語 Aiong Taigi makes videos arguing for POJ in Taiwanese, but we pasted the English explanation below.

POJ vs TL

1. ch vs. ts

Some people claim that “ts” is more accurate, since it is the same symbol used in the IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet.) However, that is not entirely true, as both “ch” and “ts” are used to represent four distinct sounds in POJ and Tailo, respectively. Only one sound is the same as the IPA symbol.

(Another is similar, but not exactly the same: “tsh” vs. /tsʰ/)

However, it is irrelevant whether a sound matches the IPA or not. In fact, the IPA is based on natural languages, not the other way around.

Furthermore, there is a larger issue: “ts/tsh” represents four sounds, and “t/th” represent another two. This means that a total of six sounds start with “t” in Tailo, which adds up to approximately 1/3 of all words that start with a consonant. Since the first and last letters of a word are the most important for pattern recognition and readability, it is clear that having 1/3 of all consonant-initial words starting with the same consonant degrades readability.

2. ek eng vs. ik eng

The letter “i” in Tailo represents three distinct sounds, while “e” represents only one. POJ balances these to two sounds each. Since the only other combination with “e” is “eh,” POJ has a good balance between distinct sounds and distinct letters: e/eh, ek/eng, i/in, ip/it. Tailo does not: e/eh, i/in, ip/it, ik/eng.

The letter “i” is also the most frequent vowel in either system, and Tailo exacerbates the problem by again bringing it close to 1/3 of all vowel occurrences.

3. oa oe vs. ua ue

These two sounds are “o”, not “u”. Tailo appears to use “u” in order to match the Mandarin Zhuyin character,「ㄨ」, which makes little sense for the orthography of a different language.

4. ⁿ vs. nn

The nasal symbol changes the quality of a vowel. It is not a separate sound in and of itself. Many languages with nasal vowels use a diacritic, like a tilde (~), to denote the nasal sound. Some variants of POJ use this as well. A superscript “n” is similar to a diacritic, and makes sense in this context as well. The contrast between a single “n” (a consonant “n” sound) with a double “nn” (a nasal vowel sound) is relatively low and makes it difficult to distinguish at a glance, again decreasing readability.

Tailo’s “nn” also significantly increases the frequency of n’s to over 40% of consonant-final letters, far and away the single most-used final consonant.

5. o͘ vs. oo

Many languages that use the Latin script utilize diacritics to help distinguish between similar vowel sounds. Some languages, like German, have actually actively transitioned away from multi-vowel spellings in favor of diacritics. Standard German now prefers diacritics whenever possible (in some cases where only ASCII characters are permissible, multi-vowel spellings may be used instead).

One final note: the balance between “straight” and “round” shapes in an orthography also seems to be somewhat important. POJ here again strikes a much better balance than Tailo, with the “c” and “e” being rounder than the “t” and “i” (ch, ek vs. ts, ik). In my experience, this also contributes to the feeling that POJ is clearer and has better readability than Tailo.

How can I learn Taigi?

Check out the awesome podcast, Bite-Size Taiwanese (They use TL):

No one in Taiwan call Taiwanese “Hokkien ” Taiwanese call it Taigi or Taiwanese Southern Min. Hokkien is Singaporean name.

LikeLike

I would recommend against using the term “Mandarin characters”. Chinese characters exist as a writing system independent of spoken language, so they should not be named after one Chinese language. Especially considering they have existed long before Middle Chinese developed into Mandarin.

LikeLike

Taiwanese NOT Hokkien. Self-respect is lacking. The very fact that there’s a separate term called Taigi denotes a separate ethnic as well as linguistic identity. If Taigi or Taiwanese = Taiwanese Hokkien, then the following should also stand: (which neither linguists nor any speakers of following languages would ever agree)

Africaan = African Dutch

Inuktun = Greenlandic Inuktitut

Karelian = Russian Finnish

Urdu = Pakistani Hindi

Maltese = Maltese Arabic

Karakalpak = Karakalpak Kazak/Uzbek

Adyghe = Adygean Kabardian

Meänkieli = Swedish Finnish

LikeLike

Great there is a post about this topic, and you forgot to mention the truth that for tens of years there were only 3 TV channels aired in Taiwan, controlled by the government, that is sick.

BTW speaking of the “Han ethnicity”, actually there was no identity as “Han” back then among the civilians, the identity with its vague defs are not based on the rationale, it’s still an arguable topic since most of the people have never or were forbidden to know more and think more about this identity issue, actually in the standard of these “漢Han people人” or “華Chinese people人” interpretation, Korean, Vietnam, Japan and maybe so on can also be included and that doesn’t make any sense as Taiwan being included (BTW Hong Kong either, even today, most of them don’t use the word “Han people” to interpret the history)

LikeLike